This year of our Lord 1876, I, Miranda Jacobsen write this my confession. I attempt to clear my conscience prior to my death.

My story begins a year ago, on All Saint’s Eve; a cold night, and one which I spent very much alone. My father had died just a few weeks earlier, of a terrible catarrh in the chest, and we had buried him in the Stull Church Graveyard. He was a cruel man, and few attended the services, those few who don’t still blame him for the death of my mother, gone these six years.

He worked her to death, never sparing her even when she was late into her final months of pregnancy. This was her seventh, all the rest besides me having ended in miscarriage, due to overwork and poor nutrition—my father was a skinflint with food. My mother had been hauling wood all day for the coming winter when her pains began. She tried to make it into the house, but something went dreadfully wrong, and I found her behind the shed, her skirts soaked in blood when I returned from school. I held her in my arms while the life leaked out of her, and she died a few moments later. My father had long looked for a reason to take me out of school, and he did so with haste thereafter, and at age 15 I surrendered my dream of completing my education and becoming a nurse. I became instead his unpaid drudge. In these past seven years, I have been kept clothed and fed, just barely, and have had a roof over my head, but no kind word was spared, no joy allowed, no extraneous conversation, merely orders, commands, work, work, and more work.

It was summer last that the peddler came through town, and my father let loose a few coins for purchase of household necessities. I bought the things he asked, save one—a tin bucket—and told him later the peddler had just sold his last one to a Mr. Strass, a neighbor up the road. My father cursed both the peddler and the neighbor and asked me for the remaining coins. I impressed upon him that the price of the other goods had risen and that there were no coins left. I hid from him the fact of my other purchase, which I began to use nightly to season his stew. Shortly thereafter, he began to waste away, as if his cruelty was eating him from the inside out, and became pale and wan. It was not a month later that he succumbed to illness, as he would sooner die than pay a doctor. In this, he was accommodated.

I enjoyed a period of relative quiet then, with the church aiding in my support, as I had no other family. They allowed me to live on at the cabin, as they felt sure they could make me a match. I was, after all, 21, able-bodied, a good worker, and unblemished of face.

I lived contentedly, taking in sewing and washing, lending my hands to those who needed help with canning and preserving, while the church elders searched for a suitable Christian man who could sustain my wellbeing. In spite of the fact that I felt no real loss, and needed to make a hasty match, it was felt that my attendance at the All Saint’s Eve dance would be unseemly, so soon after my father’s death, so I remained in my cabin alone.

I had finished a simple dinner of soup and bread when I heard a knock on the door. I opened it to find a stranger, a tall dark man with deep-set eyes who smiled at me.

“Miss Jacobsen?”

“Yes, sir, do I know you?” I pulled the door to a bit, stepping back.

“Pastor Hollings sent me over. He felt a bit sorry that you are being kept from the dance, and has wished for some time for me to make your acquaintance. He thought that it would be a fine time for us to meet.”

“Unchaperoned? That seems a bit…” I trailed off.

“Well, my dear, he has reason to trust me. I am the son of his sister.” He smiled, again, quite charmingly.

“Oh,” I said, a bit flustered yet relieved, “do please come in.” I opened the door widely and when he passed by, I smoothed my hair and pinched my cheeks to make the color rise. “Are you a man of the church as well, sir?”

“No, no, I wouldn’t say that.” He smiled pleasantly, but did not volunteer further information.

“Please, come and sit down and have a cup of tea,” I said, motioning toward the table. He took a seat and I bustled around getting the kettle on. I felt his eyes on my every move.

Talk was exchanged, we drank our tea, and I began to feel a glimmer of hope. This man was educated, cultured, and witty—all qualities my mother had possessed and my father had tried to eradicate in her and in me. I could feel heat in my cheeks as I spoke to him. My father’s death was mentioned.

“Yes, it was…strange. Some sort of wasting illness. He didn’t take to doctors, so I never found out the cause.”

“Perhaps something he ate,” he said, smoothly, smiling at me. His eyes bored into mine. “But then, I imagine you are a wonderful cook.” I blinked, and shook myself a bit.

“I have had lots of practice, Mr.—I don’t believe I heard your name, Mr.--?”

“I am Mr. Damon,” he said, and extended his hand toward me. I clasped it, expecting it to be warm, as he was seated directly next to the fire, but it was ice cold. I pulled my hand from his grip.

“Well, Mr. Damon, I expect you need to be getting back to the dance, and I need to be getting on to bed. I’m sure there are many young ladies waiting for the pleasure of your company.” I rose to show him to the door, and he followed.

“You flatter me, Miss Jacobsen,” he said. As we approached the door, his arm came over my shoulder and around my throat. “Shall we dance, Miss?”

My hands clawed, reaching toward the door, but I was pulled up and off my feet as he dragged me back into the room. His hot breath was on my neck, his arm pressing the air from my throat. The room spun.

“You’ll make a pretty bride, Miss, but I don’t know as I would allow you to cook for me. Arsenic, isn’t it?” Not exactly to recipe, I would say.”

Panicking and unable to breath, I felt my body going limp as I lost consciousness. Was this my father’s spirit, back for revenge? My last thought was of my mother, her bloody skirts and pale skin. So be it.

I awoke on the bed. I cannot say exactly what transpired in that room, but my neck was ringed with bruises and I could barely move. I have a vague recollection of awakening, but it must have been a dream, as atop me in the bed was a creature with red eyes and dreadful features, something not of this earth. Overcome, I once again slipped into a swoon.

I kept to my home for several days until the bruised faded, and after church the next week, I spoke to Pastor Hollings.

“Did you enjoy your nephew’s visit?” I said, forcing a smile to my lips. He looked puzzled.

“I have no nephews, just the one niece,” Pastor said, looking at me strangely. “Are you feeling quite all right, my dear?” I assured him of my health and returned home. Many sleepless nights ensued, and my dread increased when I realized it had been two months since I had experienced my monthly courses. Out community did not look fondly upon bastard children, and how could I explain what had transpired on that wretched night without being thought touched or feebleminded? I did not wish to end up at the lunatic asylum in Topeka.

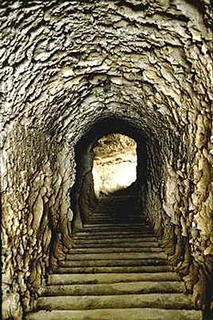

I remained as long as I could in Stull proper, until such time as my belly began to swell despite severe restriction of my victuals, and then I told Pastor Hollings that I was leaving town for a bit, to visit a distant aunt, twice removed, who I had located recently. In truth I went to the forest, and there built myself a shelter among the trees and brambles. A thin layer of snow lay on the ground, and I dug as deep a hole as I could in my condition. I survived on the foodstuffs I had carted to the forest over time; canned and preserved goods I had put up the year prior, and water from the creek nearby. My hair became a tangle, my clothes dank and musty. Several times I spotted nearby hunters or children and had to dash to the safety of a nearby cave I had found in the side of the riverbank. Spring turned gradually to summer, and I wore only my shift, filthy and torn it was, but cool, and I bathed in the creek at night under the moon. I lost track of the days.

Finally, I was awakened one night, a dark and moonless night, by my pains and a rush of water into my bed. After many hours of labor, moaning and writhing by myself in the woods, the child slid free. I lay, spent, upon the quilt. Upon hearing my babe cry, I forgot my misery and turned to him. As I picked him up to cradle him to my breast, I could see his face. His eyes were blood red, and glowing with all the evil of his father and he had a mouthful of tiny sharp teeth, which made toward my breast. Screaming, I threw him down on the blanket and turned away, crying and shivering with fear and loathing. I took the thing outside down to the creek, and held it under the water, allowing the current to cleanse the birthing fluids from the tiny body, and cleanse the evil from my life. When the child stopped struggling, I bathed and buried my bloody rags, and bundled up the child to take it to the cemetery. A burial on sacred ground was the only chance I could offer the little thing, the only chance of salvation. I made my way quietly to the Stull cemetery and dug a small hole. I wrapped the body in a rag and tucked the bottle of arsenic I had carried for many months next to it, and covered them both with earth. I arranged the grasses to appear undisturbed. As a gardening project had recently been accomplished by the Ladies’ Auxiliary in the Churchyard, the slight disruption would not be noted. I returned to my home, bound my leaking breasts, and bathed, combing the tangles out of my hair after several hours work.

The next day I visited Pastor Hollings, to tell him of my return home. He greeted me gladly, and told me all the latest news of the town.

“Be careful, Miranda,” he said. “A strange presence has been seen in the woods hereabouts of late. Keep the door tightly locked.”

My ordeal was over. I waited for my life to resume…the matchmaking and care of the community continued to be lavished upon me, as my food and funds grew ever more meager. I continued to work for others, but was often absent, almost in a trance, and people began to talk. I was extremely tired, as my nights were a torment of dreams, evil dreams in which I relived the attack, the birth, and the moment when the life went out of the devilish spawn beneath my hands. I lay awake many nights, praying for deliverance, but God has forsaken me, I fear.

I began to hear voices. “Murderer. You killed my child. I am coming for you, Miranda.” My nights continued to unravel, and I noticed my neighbors whispering behind me as I walked. I started at the least sound, the least unexpected event.

As the year began to die, I waited for All Saint’s Eve with dread. I was more and more distracted and fretful, and there were murmurings among the townspeople of sending me to the asylum. My dreams became more and more vivid, until I could scarce tell when I was awake, and when I was asleep. My evil tormentor often stood in the half-dark corner of my room, red eyes glowing, unpleasant smile on his lips, staring at me. “I am coming for you.”

This morning, I rose early, having lain awake for hours in torment. I had promised Pastor Hollings that I would bring bread to the church for the evening communion, and planned to deliver it early. As I approached the churchyard I heard the voice in my head, louder and louder. I began to run, to try and rid myself of the foul presence, hoping the churchyard would provide shelter. Instead, as I approached the church, I spied a bundle on the front steps. I stepped closer, with dread clawing at my heart and innards. I could see a form within the bundle, and recognized the sheet I had wrapped the child in, torn and filthy though it now was. Lying next to the bundle was the arsenic bottle. Beneath the bundle, written in what appeared to be blood, was my name, MIRANDA. I stumbled to the bushes nearby, and retched up my breakfast. Across the churchyard I saw Pastor Holings emerge from the rectory and startle visibly as he saw me taking ill in the bushes.

“Miranda?” he said. “Child, are you ill?” His voice carried across the vacant churchyard. I looked at him with despair, and did the only thing I could. I ran.

As I entered the wood, brambles tearing at my clothes, I heard the voice in my head, laughing with maniacal pleasure. I ran until my legs could carry me no further. I was near a small home in the woods, and exploring, it appeared there was no one at home. I entered the house and found paper and this quill, and taking only that I traveled on my way, deeper into the wood. I was now doomed, I knew, and would not be welcomed in the town of Stull again. “Nor anywhere, miss.. Anywhere but hell!” The voice whispered inside my skull, filling my chest and belly until I vomited with the pain of it. I could feel the evil growing within me, the girl that I once was fading with the afternoon light. I made ready.

There is no hope for one such as me. Have mercy upon my soul.

This account was discovered on All Saint’s Eve, 1876, in a wood outside Stull, Kansas. The words you read were written on the parchment in blood, the blood which flowed from Miranda Jacobsen’s fingertips after she pricked them deeply with locust thorns. Miranda was found hanging from a tree nearby, having torn and braided her cloak into a rope. Fixing herself to the tree, she jumped from a nearby rock. She did not die immediately, but struggled to claw the rope from her throat. Authorities discovered a partially decomposed newborn infant along with a bottle of arsenic on the steps of the Church at Stull on the same day.

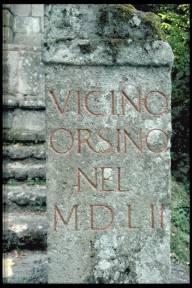

Each year, on All Saint’s Eve, October 31, Miranda Jacobsen returns to the woods around Stull, and her cries of agony as she suffocates, hanging from the tree, can be heard in the hollows and hills. Her terrible attacker, who is widely thought to be Satan, returns as well. He searches the churchyard for his child, who, following autopsy was reburied at the State Cemetery for the Poor along with Miranda, thirty miles away. Stull is thought to be one of the seven gates of hell, as Satan chose it for the birthplace of his heir. Miranda’s name is often found the next morning, written in fresh blood, on the remains of the old church foundation, which was demolished a number of years ago.